In the Driftless Area, ice skating doesn’t feel like a novelty or a polished winter attraction. It feels earned. When cold settles into the valleys and the backwaters finally lock up, there’s an unspoken readiness that spreads through towns and rural neighborhoods alike. Someone checks the ice. Someone else sharpens their blades. And then, quietly, winter opens a door.

That feeling—of waiting, watching, and finally stepping onto the ice—connects us to a history far older than any rink or scoreboard. Ice skating didn’t begin as sport or art. It began as survival.

Thousands of years ago, people in northern Europe faced winters just as demanding as ours. Archaeological evidence from Scandinavia, Finland, and Russia shows that by around 3000 BCE, humans were strapping animal bones—horse, elk, even cattle—to their feet to cross frozen lakes and rivers.

These early skates didn’t carve into the ice the way modern blades do. Skaters pushed themselves forward with poles, trading speed for efficiency, moving across frozen landscapes because they had to.

That instinct still resonates in the Driftless. This is not a flat place. Rivers bend, cold pools in coulees, and ice forms unevenly. You learn to read winter here—where it holds, where it thins, and when it invites movement.

Skating changed dramatically in the Middle Ages, especially in the Netherlands. By the 13th and 14th centuries, wooden skates fitted with iron runners allowed for smoother gliding and real control. Frozen canals became winter highways, then social spaces. People raced, skated for pleasure, and gathered on the ice simply because it was there.

That was the turning point, when skating shifted from necessity to joy.

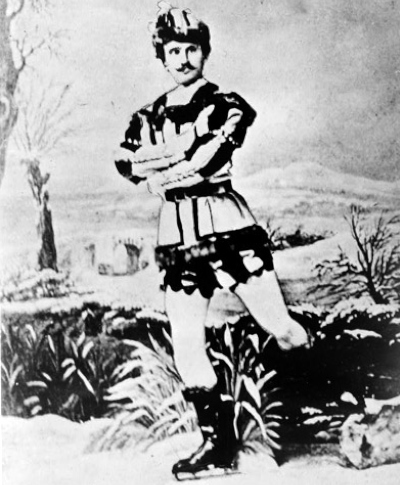

By the 1700s and 1800s, skating was becoming formalized. Scotland formed the first known skating club in 1742. England published the first skating instruction manual in 1772. Steel blades replaced iron, allowing sharper turns, spins, and eventually jumps. In the mid-1800s, American skater Jackson Haines introduced flowing movement and music, shaping what we now recognize as figure skating.

By the 1700s and 1800s, skating was becoming formalized. Scotland formed the first known skating club in 1742. England published the first skating instruction manual in 1772. Steel blades replaced iron, allowing sharper turns, spins, and eventually jumps. In the mid-1800s, American skater Jackson Haines introduced flowing movement and music, shaping what we now recognize as figure skating.

Around the same time, ice hockey was taking shape in Canada, blending skating with stick-and-ball games played on frozen ponds. Speed skating evolved from racing traditions in Scandinavia and the Netherlands. By the early 20th century, skating had reached a global stage, with figure skating debuting in the Olympics in 1908 and speed skating included in the first Winter Olympics in 1924.

Artificial indoor rinks would later make skating accessible year-round and far beyond cold climates. But even with climate control and bright lights, outdoor skating never lost its gravity—especially in places where winter still shapes daily life.

That difference is amplified in the Driftless. Unlike much of the Upper Midwest, this region escaped the last glaciers, leaving steep ridges, limestone bluffs, spring-fed streams, oxbow lakes, and wide river backwaters. When winter freezes these features, skating becomes immersive—you’re not just circling ice, you’re moving through terrain and weather.

Across the Driftless, outdoor rinks remain the backbone of winter community life. Town parks in places like Viroqua,WI, Decorah, IA, Prairie du Chien, WI and Winona, MN flood ice each winter, creating spaces where pickup hockey games form organically and kids learn to skate under dim park lights. These rinks aren’t flashy. They don’t need to be. They work because they belong to everyone.

Across the Driftless, outdoor rinks remain the backbone of winter community life. Town parks in places like Viroqua,WI, Decorah, IA, Prairie du Chien, WI and Winona, MN flood ice each winter, creating spaces where pickup hockey games form organically and kids learn to skate under dim park lights. These rinks aren’t flashy. They don’t need to be. They work because they belong to everyone.

Then there are the rare, perfect wild-ice days—the ones people talk about for years. When conditions line up, sheltered lakes, flooded fields, and slow-moving river edges freeze smooth and clear. In the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge, backwater areas can sometimes offer long, quiet skates framed by bluffs, cottonwoods, and the sound of ice shifting beneath you. Smaller spots—Lake Onalaska or rural county park lagoons—can feel almost sacred on calm winter mornings.

Skating here isn’t just recreation. It requires attention—listening for cracks, watching the color of the ice, feeling vibration through your blades. That balance between joy and caution hasn’t changed much since bone skates crossed prehistoric lakes.

Ice skating’s long history is still unfolding. Today, ice skating lives in many forms—figure skating, hockey, speed skating, and casual laps with friends—but its core remains the same. It’s a way of meeting winter on its own terms, of finding movement where others see stillness.

Ice skating’s long history is still unfolding. Today, ice skating lives in many forms—figure skating, hockey, speed skating, and casual laps with friends—but its core remains the same. It’s a way of meeting winter on its own terms, of finding movement where others see stillness.

In the Driftless Area, where land and water refuse to be simple, skating feels especially honest. Ice comes late and leaves early, which means you don’t take it for granted. Every skate is temporary, and that’s part of the draw. Out here, between bluffs and backwaters, skating doesn’t feel like something we inherited. It feels like something we’re still earning, one winter at a time.

By Riley Johnson