Cover Story by Joy Miller (03/21) –

Cover Story by Joy Miller (03/21) –

When I dove deep into the Driftless, I discovered a farming and food scene that piqued my curiosity. I’d ditched my urban life when I fell in love with an organic farmer and found myself wanting to take a closer look at the allure of the region that had captured my heart. I was working toward my Masters degree with Johns Hopkins University at the time, studying Liberal Arts. I’d been focusing on social justice classes like: Ethics for a Multicultural World, Family in Cross-Cultural Perspective, and America’s Cultural Diversity: The History of Race and Ethnicity in the United States. I read back to back books that further revealed the dark underbelly of our culture: systematic oppression, capitalism, and endless policies that fix the game. My mind was running circles around the idea of culture and ethics, and from what I could see, we were in dire need of some culture correction, and agri-culture was no exception. I narrowed my focus to farming and food justice, and when it came time for my graduate research, I turned to study the Driftless food community in a project called, “Socially Responsible Food and Ethical Food Consumerism: A Community Based Research Project in Driftless Wisconsin”. I saw a glimpse of something different here, and I needed to dig to the root of it to find out if maybe it could be replanted around the country.

I wanted to be a part of the growing food justice movement in response to the inherent inequities and damaging components of the U.S. food system. My research would examine values toward socially responsible food and practicing ethical food consumerism in the Driftless community of Southwestern Wisconsin. I conducted interviews, focus groups, observations, and surveys in grocery stores, food co-ops, restaurants, fields, and barns. I asked a series of questions related to people’s level of concern about different categories of food justice like agricultural chemicals, GMOs, antibiotics/hormones, farmer wages, buying local, animal treatment, environmental damage, and carbon emissions. I followed with a question about how much of the food they buy is organic, non-GMO, antibiotic/hormone free, FairTrade, local, humanely raised, regeneratively grown, and low emission.

I wanted to be a part of the growing food justice movement in response to the inherent inequities and damaging components of the U.S. food system. My research would examine values toward socially responsible food and practicing ethical food consumerism in the Driftless community of Southwestern Wisconsin. I conducted interviews, focus groups, observations, and surveys in grocery stores, food co-ops, restaurants, fields, and barns. I asked a series of questions related to people’s level of concern about different categories of food justice like agricultural chemicals, GMOs, antibiotics/hormones, farmer wages, buying local, animal treatment, environmental damage, and carbon emissions. I followed with a question about how much of the food they buy is organic, non-GMO, antibiotic/hormone free, FairTrade, local, humanely raised, regeneratively grown, and low emission.

Overall, Driftless consumers reported high levels of concern about food justice topics in the survey. In almost every category of concern, the largest number of participants marked an extreme level of concern: 51% were extremely concerned about pesticide use, 43% were extremely concerned about GMOs, 57% were extremely concerned about antibiotic/hormone use in animal products, 56% were extremely concerned about the humane treatment of animals, and 61% were extremely concerned about environmental damage. The only question of concern in which the largest number of participants did not report extreme concern was in the category of carbon emissions, where 34% reported extreme concern and 41% were moderately concerned. For all survey questions, “not concerned” had a low response rate, ranging only from 2% to 10% of responses. The high levels of “extreme concern” and low levels of “no concern” confirmed my hypothesis that a portion of the Driftless population has a high level of food conscientiousness, but did it show up in their grocery cart?

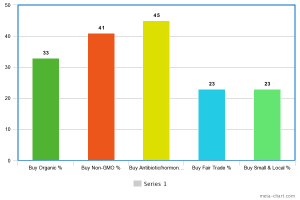

Even in a community with a rich local food economy and high levels of concern about food justice issues, there are still barriers to purchasing foods that align with personal values, and as I hypothesized, the primary barrier is price. However, the survey results showed the largest group of participants responded they purchase 75% to 100% of foods that align with their values in each category. Thirty-three percent of consumers almost always buy organic, 41% of consumers almost always buy non-GMO, 45% almost always buy antibiotic/hormone free, 23% of consumers almost always buy foods that intentionally prioritizes farmers like Fair Trade, and 23% of consumers almost always buy small and local. Even given that some participants may have overestimated their purchasing patterns, these results show relatively high levels of ethical food consumerism, but what I was really curious about is why?

Even in a community with a rich local food economy and high levels of concern about food justice issues, there are still barriers to purchasing foods that align with personal values, and as I hypothesized, the primary barrier is price. However, the survey results showed the largest group of participants responded they purchase 75% to 100% of foods that align with their values in each category. Thirty-three percent of consumers almost always buy organic, 41% of consumers almost always buy non-GMO, 45% almost always buy antibiotic/hormone free, 23% of consumers almost always buy foods that intentionally prioritizes farmers like Fair Trade, and 23% of consumers almost always buy small and local. Even given that some participants may have overestimated their purchasing patterns, these results show relatively high levels of ethical food consumerism, but what I was really curious about is why?

A region that escaped glaciation, the Driftless is known for its steeply dissected terrain and extensive network of streams. These features confine agriculture to the ridges and valleys. The “limitations” of the Driftless topography put farmers in a precarious position when agricultural policy shifted in the 1970s. They couldn’t heed the call of the secretary of agriculture, Earl Butz, who told farmers to “get big or get out” and plant commodity crops “fencerow to fencerow”. The slope of the land wouldn’t allow it. Our topography works wonderfully for small scale farming, but the ridgetop and valley farms can’t sprawl into mega farms like flatter areas of Wisconsin.

Instead, a group of hippies and back-to-landers who saw both the beauty of the region and the injustice of the system forged another option.

Why are the hippies and back-to-landers important? Social circles have the ability to redefine cultural norms within their group, creating a counterculture. One counterculture group, who has redefined norms about food is “the hippie culture”. Jonathan Kauffman’s (2018) book, Hippie Food: How Back-to-the-Landers, Longhairs, and Revolutionaries Changed the Way We Eat, tells a story of a set of values that extended to food choices beginning in the 1970s. Hippie food was a rejection of social norms surrounding food like the use of pesticides. They wanted to take food back to its pre-industrialized roots and approached food as activists fighting capitalism. They considered eating brown rice to be a political act and refused the “deathlike values” of the mainstream food system (Kauffman, 2018). Many hippies wanted to get out of the city and into farming and homesteading. Some of them became organic farmers in the Driftless region and have been an integral part of establishing socially responsible food values in this area. They were a counterculture drawn to food who recognized that, “the industry that is in control of providing food for the people is in fact ripping them off” and “the food industry is one small part of the larger corporate structure whose only interest is in making money” (Kauffman, 2018). They refused to be industrial chemical farmers. They “bucked the system” in two big ways.

Why are the hippies and back-to-landers important? Social circles have the ability to redefine cultural norms within their group, creating a counterculture. One counterculture group, who has redefined norms about food is “the hippie culture”. Jonathan Kauffman’s (2018) book, Hippie Food: How Back-to-the-Landers, Longhairs, and Revolutionaries Changed the Way We Eat, tells a story of a set of values that extended to food choices beginning in the 1970s. Hippie food was a rejection of social norms surrounding food like the use of pesticides. They wanted to take food back to its pre-industrialized roots and approached food as activists fighting capitalism. They considered eating brown rice to be a political act and refused the “deathlike values” of the mainstream food system (Kauffman, 2018). Many hippies wanted to get out of the city and into farming and homesteading. Some of them became organic farmers in the Driftless region and have been an integral part of establishing socially responsible food values in this area. They were a counterculture drawn to food who recognized that, “the industry that is in control of providing food for the people is in fact ripping them off” and “the food industry is one small part of the larger corporate structure whose only interest is in making money” (Kauffman, 2018). They refused to be industrial chemical farmers. They “bucked the system” in two big ways.

They went collective and they went organic. Local farmers realized they would have to cooperate to compete, so they formed the Coulee Region Organic Produce Pool (CROPP), better known as Organic Valley in 1988 in La Farge. Wisconsin is now the number two producer in organic agriculture, leading the nation in organic dairy products. The presence of what is now the nation’s largest organic cooperative has permeated this small rural community with a high level of awareness about everything from land ethic to the economic viability of organics.

They went collective and they went organic. Local farmers realized they would have to cooperate to compete, so they formed the Coulee Region Organic Produce Pool (CROPP), better known as Organic Valley in 1988 in La Farge. Wisconsin is now the number two producer in organic agriculture, leading the nation in organic dairy products. The presence of what is now the nation’s largest organic cooperative has permeated this small rural community with a high level of awareness about everything from land ethic to the economic viability of organics.

Since the formation of Organic Valley, the Driftless community has continued to embrace the cooperative business model. Through my research, I learned the Driftless regions of Minnesota and Wisconsin are the heart of co-op country. There are over 15 cooperatives in Vernon County alone. Wisconsin was the second in the nation after Michigan to approve cooperative legislation and these social values toward cooperative action are rooted in the Scandinavian and Norwegian cultures of the immigrants who came to this area. In the survey, I asked, “Has the presence of cooperative business models, like Organic Valley, and their values and practices in the community influenced the way you think about farming and food?” Out of all respondents, 88 % responded affirmatively. Of the 22 people who answered no, 5 of those individuals wrote that they already valued the cooperative business model before it became prominent in the community. The prevalence of positive responses confirmed my hypothesis that the presence of cooperatives has had an impact on food values. These collective social values, which go against the mainstream economic trends of capitalism and competition, set the Driftless Area apart from other agricultural areas of Wisconsin and make it a unique area of study concerning food values.

A craggy topography, back-to-landers, and cooperative economics weren’t the only factors I found to influence Driftless food values. I had one more hypothesis, and it circled back to unjust policy. I hypothesized that a history of agricultural injustice concerning farm policy has motivated a portion of the Driftless community to embrace more socially responsible food values. The dairy crisis, as it has been called, is linked directly to policy and has caused massive shifts in agriculture. The crisis escalated in the mid-80s after the 1980 Farm Bill began to phase out milk parity. By 1983 parity was totally eliminated in setting the support price for milk which neglected the cost of production. Farmers were at the mercy of the free market and could not financially sustain their operations, so they began to sell their herds and land, losing their livelihoods and homes. In the survey, participants were asked the following, “During the dairy crisis of the mid-80s, many small dairy farmers of the Driftless community went out of business due to food policy change. Does this history impact the way you think about farming and food?” Of all respondents, 62% answered yes. The majority of respondents mention that the crisis has motivated them to support local, small farmers, and co-ops. Appreciation for the small farmer and recognition of injustice done were also mentioned. A number of Driftless residents mention how the crisis has affected them personally, which has deepened their values about farming and food. One participant said, “I think about the dairy crisis of the 80’s often as it personally affected my family. I am very concerned about our local farmers and the struggles they’re facing. I try to support our local farmers as often as possible.”

Community appreciation, recognition, and consumer support are vital to the survival of the small farmer. These attitudes represent a communal value system that looks beyond the individual toward a social appreciation of farming, which is a crucial lack in our mainstream food system. The fact that so many residents are motivated to take consumer action points to the strength of inner initiative and social circles in purchasing behavior. Changes in behavior require a shift in consciousness. Living through the personal or community experience of agricultural injustice seems to be associated with a shift in consciousness. This shift, which elevates inner initiative to support farmers, has a more profound effect on purchasing behavior than external factors like outside information, marketing or recommendations.

In 1992, Smithsonian magazine nicknamed Viroqua ‘The Town That Beat Walmart’ because “three years after Walmart came in, the number of downtown small businesses actually increased” (Renwick, 2018, para. 19). Generally, when Walmart comes into a rural area, small local businesses suffer immensely, but once again, the Driftless community came together and supported each other in revitalization initiatives to fight back against the status quo of corporate control. As a result, Renwick (2018) writes, “In the last few years, this part of the state has instead seen something of a renaissance, as natives, returnees, and newcomers have created a thriving micro-economy, one that’s primarily built around local food” (Renwick, 2018, para. 5). The social strength of a cooperative community like this is getting attention and drawing like-minded individuals to the area which invigorates the region with momentum to continue embracing a healthier food system.

As an aspiring food justice activist in search of a catalyst for the movement, I believe that a portion of the Driftless community embodies elements of catalyst potential including; socially responsible food values, ethical food consumerism, internal motivations, social concern, farmer support, and economic cooperation. These social values could be spread to other rural farming communities who have faced similar food justice struggles. In my opinion, social values are at the heart of social movements, and the Driftless community members I surveyed and spoke with expressed an expanded concern for social wellbeing. I have discovered that deep social values which carry the clout to impact consumer behavior do not come easily in a culture whose value system is based in capitalism, consumerism, and individualism. The social values in this community were born out of hardship and struggle and do not follow a norm but attempt to create a new one. The Driftless community has forged a value system from inner initiatives, self-identification, personal connection, and supportive social circles.

If we hope to advance the food justice movement, I suggest we follow their lead. When seemingly faced with a duality of choices, we must creatively collaborate to give birth to a better option. This could mean collectively revitalizing small farming and supporting small farmers in taking food, power, and agency back from large corporations. In a society disconnected from food and farming, we must strive to reconnect to the roots of what feeds us all. This could mean opening farms up as social spaces where people can identify with and make personal connections with food and farming to strengthen their internal motivators and build community around food. In a culture that disregards and disrespects small farmers, we must honor, support, and advocate for their livelihood. This could mean raising awareness of struggling farmers, creating programs for farmers to transition to organic, or helping small farmers form cooperatives. In an economy dominated by capitalist greed, we must seek out alternative business models that share the wealth and work together. This could mean reevaluating food as a capitalist commodity, emphasizing the social aspects of food, and transforming from a capitalist to a more cooperative food economy. In essence, we must revitalize our social value system to begin setting things right in our food system. I dove deep into the Driftless and discovered a curiosity. I came out the other side with an idea.

Kaufmann, J. (2018). Hippie Food: How back-to-landers, longhairs, and revolutionaries changed the way we eat. New York: William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins [Audiobook].

Renwick, D. (2018). How did Viroqua, Wisconsin – A farm town of 4,000 – Emerge as a major Midwestern food destination? New Food Economy. Retrieved from https://thecounter.org/viroqua-wisconsin-local-food-renaissance/