By Matt Schumann –

Let’s widen the focus way back before we zoom in on Emma Big Bear. Trying to describe the life of a centuries old Ho-Chunk woman, through a web essay – to generations B, X, Y and Z – is perhaps an exercise in folly. We in 2019 might say, “Wow, it must have been hard living without (fill in the blank).” Cars, mass transit, cash cards, apartment complexes, and/or media screens of some variety. I would argue that life and our expectations; my life, your life, and the quality time we spend with it, are no more valuable or well spent than those of people living in 1910. Life wasn’t necessarily a slog. You lived it and adjusted accordingly.

Let’s widen the focus way back before we zoom in on Emma Big Bear. Trying to describe the life of a centuries old Ho-Chunk woman, through a web essay – to generations B, X, Y and Z – is perhaps an exercise in folly. We in 2019 might say, “Wow, it must have been hard living without (fill in the blank).” Cars, mass transit, cash cards, apartment complexes, and/or media screens of some variety. I would argue that life and our expectations; my life, your life, and the quality time we spend with it, are no more valuable or well spent than those of people living in 1910. Life wasn’t necessarily a slog. You lived it and adjusted accordingly.

Much of the big difference between now and then was you walked a heck of a lot more. Love of the outdoors is within the hearts of everyone; every single person alive. And if it’s not, or you feel it isn’t within you, then on some level you wish it were. To be an outdoors person for long periods of time – epic-long as in you are homeless or transient; medium-long as in you’re travelling on an extended trek, vacation, visit, or adventure; or short day-trips comprised of, say, walking 5 times up and down the aisles of a giant box store, going on hike with friends around your campsite, picking strawberries at a farm, or walking to the riverbank from church, on a Sunday, and then home again to visit a friendly neighbor – if you are walking in any of those circumstances, chances are 90% or better that you are carrying your stuff with you – commensurate and in relation-to – what your journey requires.

a lot more. Love of the outdoors is within the hearts of everyone; every single person alive. And if it’s not, or you feel it isn’t within you, then on some level you wish it were. To be an outdoors person for long periods of time – epic-long as in you are homeless or transient; medium-long as in you’re travelling on an extended trek, vacation, visit, or adventure; or short day-trips comprised of, say, walking 5 times up and down the aisles of a giant box store, going on hike with friends around your campsite, picking strawberries at a farm, or walking to the riverbank from church, on a Sunday, and then home again to visit a friendly neighbor – if you are walking in any of those circumstances, chances are 90% or better that you are carrying your stuff with you – commensurate and in relation-to – what your journey requires.

To paraphrase George Carlin: You carry your stuff. You carry your stuff with you, and then, when home, you store your stuff on shelves and put your stuff away.

Baskets.

People used to joke, “What are you majoring in College? Basket Weaving?” Ha. It’s a joke of the modern, directed at the traditional. Rewind a hundred and fifty years. Rewind to the Settler era. Rewind to the Native People’s era. Now how important are baskets? Hmm? You dissing baskets now? No. You are not. Before they were made by machines, crafts people – women, predominantly – worked hard at making baskets. Square baskets could be filed on storage shelves side-by-side. Color-coordinated bands and decoration could tell what’s in them. Fishing creels? Baskets. A tight weave and sturdy carved handles were meant to survive (ahem) For.Ev.Er. Go pick wild mushroom and ginseng for resale. Go collect eggs. Go to market with your sustainable, reusable, organic grocery transportation device? Bingo. Baskets.

Baskets were yesteryear’s luggage, Tupperware, strainers, and tool drawers. Imagine half of all your kitchen storage gone in a snap. Don’t worry Time Traveler, you have baskets.

Okay, now that we are in the proper headspace: In the 1870’s to pre-WWII, yes, machines made baskets, cabinets, shelves, and glass mason jars. Yet like old blacksmiths and tanners, wood carvers and quilt makers, a generation – a Last Generation – kept these traditional ways alive. Out of necessity, out of legacy, out of nostalgia, all true. But also because these last few of their generation were really freaking good at it. “Zen and the Art of Basket Weaving” could easily sub in for “Quilting” and “Model Ship Building” as pastimes and hobbies for people to give as legacy gifts and sell at craft shows. For the last third of her life, Emma Big Bear made hand woven baskets of tight fine construction and beauty, lived in the outdoors utilizing traditional Ho-Chunk skills, and sold – or traded – her wares to sustain herself. These included trapping, jewelry making, and wild mushroom and ginseng harvesting, but most notably baskets. These were practical baskets big and small. Easter Baskets were considered a bigger deal back then, both for the holiday and as year-round table centerpieces. She built hundreds upon hundreds of them for friends and neighbors. She lived to be a 100.

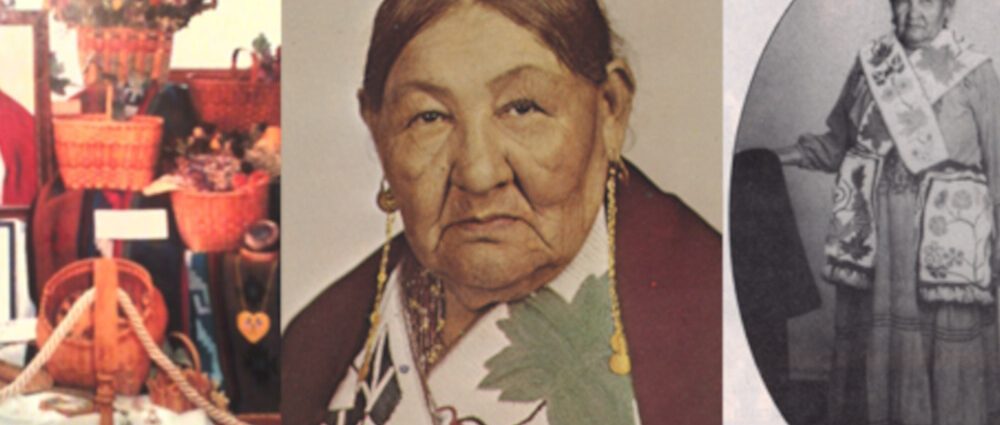

Born on 7/5/1869 or thereabouts; died on 8/21/1968. Her baskets are sought after even today in Iowa and Wisconsin’s craft and antique shows. She signed a few. They’ve appreciated in value. You know how, if you find a basket buried in gramma’s storage closet, and you squeeze it – it crinkles or feels “mushy”? Emma’s are tight. “Tight” in both traditional and current meanings. They were made of Black Ash tree logs. Ho-Chunks are native to the area, Black Ash trees are native to the area, ergo, Emma’s baskets were made in a tried and true Ho-Chunk method. The logs are stripped, pressed, and stripped again with a double handed blade. (Black Ash trees are hard to come by now as they’ve been logged for their quality and… remember hearing about the Emerald Ash Borer? Yeah. They’re jerks.) If you picture a tree cross section and its rings, pressing each ring layer made it tight. Strips would then be pulled and snipped trim. Emma was left-handed, so when finishing the basket’s top lip edge, she would wind the final thin strips in a “\” rather than a “/” as righties do. So if you’re at a flea market or in an antique shop anywhere in the Driftless or beyond – even Greater Illinois or Missouri, if you come across a tight (I mean Tight!) square basket with left-leaning hash strips at the top, you might have found an “Emma.” They have a fan-base believe it or not, and they are sought after.

The subject of her life is too big for one simple essay. But in a few paragraphs: Viewing themselves inside-out the native peoples of Wisconsin (a great many) refer to themselves as Ho-Chunk. Outside-in, European Settlers – or European Invaders, if you want to go there – referred to them as the Winnebago Tribe. (And by “go there” I’m not being dismissive. “Going there” is something everyone should do at some point. At many points, in fact, for reflection. *saved for another time*) The Ho-Chunk peoples were gathered, as best as any religious-leaning military could, and moved to Tomah, Wisconsin. This is where Emma was born.

As more settlers filled-in around Tomah, the Military were tasked with moving the Ho-Chunk south to the McGregor/Marquette area. She spent her younger years here, no doubt loving the Mississippi River Valley. Like the earth in front of a bulldozer, so did the Ho-Chunk have to move again across Iowa, through Festina, Iowa all the while skirting under Sioux Territorial borders. They were moved across the entire length of the state and into Nebraska. Later still, through Kansas and into Oklahoma. However, like the proverbial bulldozer, some of the earth was pushed out from the sides of the plow and remained behind. The push left a network of friends, relatives, and cousins dotting the way. A Ho-Chunk woman might marry a German farmer in central Iowa and stay. A Ho-Chunk man might find work in Wisconsin and stay. Whatever this northern Trail of Tears was, it wasn’t a clean sweep. It became a refugee travel route. Her father and mother divorced. Her father remained in Tomah. Her Mother remained in the McGregor area. Emma married a man who took her to Nebraska for a time. They lived a hard-scrabble life out west, but like many, she longed for a home left behind. With her husband, an American Indian named Henry Holt, they returned: a life stretched out far from home and then retracted back like a rubber band. Many towns can claim Emma Big Bear as a resident. Festina residents, some to this day, remember her there selling and trading her baskets.

Other than her community contributions which were subtle, never showy or overt, her story can be viewed from the angle of any number of socio-political opinions. Not least of which is how white people in these communities regarded Ms. Big Bear. Certainly, it must have run the gamut. But those who got to know her, loved her in their way. A few got close enough to have her over for dinner. A few she was friendly enough with that she was comfortable spending the night. After a big rain, a neighbor might say, “Go down and check on Emma and Henry and see how their doing.” After a fishing trip, a father might say to his son, “Run dis extra couple-a fish over to Emma, ya der Ziggy.”

Henry passed away in 1944, the result of catching pneumonia after falling through the ice one winter. Emma outlived him by 24 years. They had a daughter, Emiline, who was in poor health frequently. Emma and Henry became parents late in life. Emma was in her forties when she became pregnant. Emiline passed away around the same time as Henry. Emma Big Bear lived solo from 1945 until her death in 1968. In the end some friends and a pastor convinced her to move into a care facility back in Tomah. She was buried anonymously in Blue Wing Cemetery near her birthplace in Tomah, Wisconsin.

My opinion, having attended the gathering for her 150th birthday commemoration, is that the dozen or so men and women in their 70’s (out of the thirty or forty attendees of all ages) remember Emma from their youth in the way that young people at the time were raised to regard their elders with respect. For sure there is a bit of mythmaking and nostalgia going on. The same thing happens at Lambeau Field or a Mark Twain museum. I imagine some of the men back then were the seven-year-olds who approached her cautiously and said, “Gee whiz, so you’re a real Indian? And this is a real wigwam, huh? … Jeepers.” Then on the walk home, the kids would try and square the real Ho-Chunk woman that their parents knew from the community and church; the one that made four of Mom’s pantry baskets; the one who made their Easter baskets; and square that with the Indians on their TV and movie screens. They’re thankful now for the lesson.

Speaker #1 at the event was Wayne Kling, a friend of the Ho-Chunk people who became involved with researching The Bills (Wild Bill Hickock – the gambler & Buffalo Bill Cody – the carnival showman). I’m in my 40’s and I have the darndest time keeping the two of them straight! Why did they have to both be named Bill?! Anyway, I’ve come to remember Bill Hickock as the one who was shot in the back in Deadwood, South Dakota. I try to use verbal and visual cues to help me remember things, and I hate to say it, but I imagine Bill Hickock saying “Hickock!” at the moment he was shot in the back, because it sounds like the kind of thing you might make after being shot in the back. Then Buffalo Bill is the one in Annie Get Your Gun.

Clichés aside, Wayne Kling has taken some time as a researcher to track down Emma and Henry’s time in Nebraska. And… he’s been looking into a rumor that Emma Big Bear rode and did stunt riding for a season or two in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. The locations and dates match up. And Buffalo Bill had a rider on staff named “Big Emma.” Emma would have been in her late twenties at the time. It’s hard to research events and dates when Buffalo Bill kept sloppy records, if any at all, and no doubt paid his Indian performers in what? Cash? Free room and board? Mr. Kling continues his research, but it’s daunting and he’s doing it purely for his own edification. He’d welcome any lead, rumor, or research assistance that anyone could provide nationwide. Contact the Emma Big Bear Foundation for more info.

Speaker #2 was Terry Landsgaard, a local historian who not only knows the ins and outs of Emma Big Bear’s story but remembers her from his youth in Festina. He was able to succinctly describe the Ho-Chunk people’s forced relocations through the area as well as the conditions and politics surrounding Fort Atkinson. The Fort in Fort Atkinson was the pinion around which revolved all northern Indian Resettlement through Illinois and Wisconsin both pre and post Iowa, Wisconsin, and Minnesota statehood. A very animated and professorial speaker, Mr. Landsgaard brought it all back to the baskets at the end of the gathering. He’s in love with the craftsmanship of the things and heck if it wasn’t infectious.

There were other anecdotes and stories shared. Emma could spit tobacco seven feet into a spittoon and not otherwise spill a drop. Young Emma once found a cache of wild ginseng and as she began picking it realized she was in a rattlesnake pit… she had to climb a cliff to escape. A guy at church on Sunday once called Emma out for being in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, and she would neither confirm nor deny the allegation.

Within the Cobblestone Suites conference room, Rogeta Halverson sponsored the gathering as she and her family have done for a number of years. Her mom has recently passed, but her mom knew Emma. Ms. Halverson arranged a dozen long tables in a square and displayed some three or four dozen of the Emma Big Bear baskets along with articles and notable event documentation about her life. Photos and paintings of Emma. Emma’s necklaces and jewelry were displayed. One item was a great, really striking blue shirt that Emma handmade with a beaded collar and designs. Pristine, it would look cool worn by anyone today.

Ms. Halverson sponsors this gathering once a year and works through a small non-profit organization to keep the memory alive. Though she would ultimately like to find a permanent home for the Emma Big Bear collection, she and the foundation more pressingly would like to help pay for a graveside marker to commemorate Emma Big Bear’s life. It would be placed in Bluewing Cemetery up in Tomah. As of this writing, she has no cemetery headstone.

With Thanks:

- The Cobblestone Suites of Marquette Iowa for providing accommodations: https://www.staycobblestone.com/ia/marquette/

- Rogeta Halverson, the foundation, Wayne Kling, and Terry Landsgaard

- YouTube has some wonderful clips of people making Black Ash strips for baskets. Start with Echo’s http://youtu.be/yimlUtd0Pao and go from there.

Across the river in Prairie Du Chien Wisconsin, at the Villa Louis Riverside Park, there is a sculpture garden with bronze statues depicting some of the area’s famous residents. A life-sized statue of Emma Big Bear sits weaving, a strip of Ash in her hand. It’s worth stopping by as the whole Villa Louis site is fascinating and the Mississippi River Front is its usual beautiful self.

Thanks for reading.

Visit Website HERE