“The fire stick was like a paintbrush. Touch it here in a small dab, and you’ve made a meadow for elk; a light scatter there burns off brush so the oaks make more acorns.”

“The fire stick was like a paintbrush. Touch it here in a small dab, and you’ve made a meadow for elk; a light scatter there burns off brush so the oaks make more acorns.”

-Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants.

This month, the Iowa DNR released a draft of the updated Iowa Forest Action Plan. The document contains a wealth of information about the state of Iowa’s forests, outlining everything from composition (how much oak-hickory forest is out there, how much maple-basswood, etc.) to ongoing forest health issues like oak blight and emerald ash borer.

The draft also features extensive information on the types of stewardship that takes place among Iowa’s forests, with a heavy emphasis on the application of prescribed fire.

It has been fascinating to see the evolution of public opinion as it pertains to prescribed fire even over the span of my lifetime. I remember the first time I saw prescribed fire in action when I was a young lad growing up in rural Scott County. One spring morning I saw thick, black smoke pluming from a ditch just a few hundred yards from my house. Panicked, remembering that only I could prevent wildfires – which felt like a big responsibility as a kid – I ran to tell my dad that there was a fire up the street.

He explained that the county roads department was intentionally burning that ditch to get rid of the old grasses. I think, anyway. I don’t remember exactly what he said, because I was too awed by the towering flames and the seemingly insouciant roads crew carefully watching them to make sure they didn’t escape their intended boundaries.

Fast forward to today, and prescribed fire has indeed escaped the road ditches and become common practice for public and private landowners alike. Grasslands enrolled in the conservation reserve program may get a burn as part of their “mid-contract management.” Public prairies get burned at regular intervals to reset the successional clock and keep grasslands from turning into shrub land or forest land.  But the Iowa Forest Action Plan outlines another application that hasn’t yet caught on to the same degree, despite the urgent need for it in many forest lands. Woodland burns, particularly in oak forests, may play a key role in reversing the decline of oaks in Iowa.

But the Iowa Forest Action Plan outlines another application that hasn’t yet caught on to the same degree, despite the urgent need for it in many forest lands. Woodland burns, particularly in oak forests, may play a key role in reversing the decline of oaks in Iowa.

Woodland burns represent a whole different animal from the prairie burn. When one lights up a grassland, the fire advances rapidly with huge flame heights. The prospect of dealing with that kind of fire behavior in a woodland with copious amounts of dead and downed trees seems daunting enough to keep many timber owners from taking advantage fire’s unparalleled efficiency in managing invasive species, keeping brush down, and most importantly, propagating oaks.

In reality, woodland burns require a little bit more planning, but the burns tend to have less wild behavior. Leaf litter typically burns slowly, and even a strong headwind doesn’t make fire sprint across the burn unit like prairie burns. Leaf litter carries a much shorter flame height, allowing narrower firebreaks to suffice. The burn crew can get by with a leaf blower or rake clearing a couple feet of litter down to mineral soil for adequate containment.

Burns in the woods also do not have quite so definite an endpoint as the prairie burn, a feature that can further the feelings of unease. Where a prairie fire ends when most or all of the vegetation is consumed, large downed logs or standing dead trees may smolder for days after a burn in the timber. So long as the smoldering log roll out of “the black,” AKA the burned area, they don’t present much danger of escape. A trench on the downhill side will eliminate the risk of a log rolling out of the burn, but larger snags may need vegetation cleared around their base or to be felled before the burn so they don’t ignite and throw embers on the wind.

But perhaps the biggest issue that keeps people from burning their woods is just the plain old disappointment when they first try a burn. Especially for those accustomed to the awe-inspiring inferno of a prairie burn, watching tiny flames creep agonizingly slowly through a woodland can seem a little lackluster. It’s spotty, it’s not terrifically hot, and it takes all day.

That lackluster performance keeps people from trying again, but there’s the rub: a mediocre burn one year often sets the table for much better burns thereafter. Fire begets fire. It’s a process understood and practiced by indigenous peoples for thousands of years. Birch bark provided a critical firestarting material for the Anishnabe people of the upper Midwest; birch also just so happens to thrive in recently-burned areas.

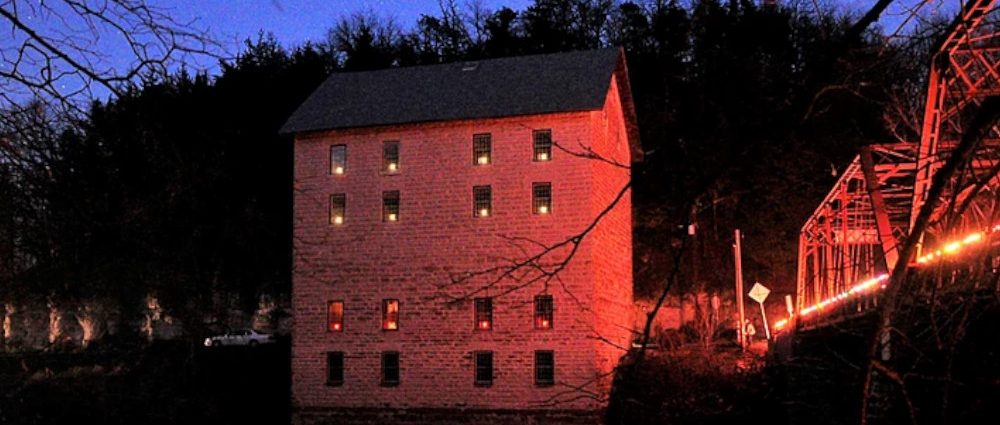

We have a case study right here in Clayton County at the Motor Mill historic site. We’ve spent the last few years working on restoring an oak savanna along the equestrian trail in the south unit. In the fall of 2019, we thought the understory looked ready to carry a burn. We found a good weather window and lit it off, certainly the first fire that landscape had seen in many decades. Only about half of the target area burned.

But this summer, what came back in that burn area was astounding. The once-barren forest floor sprung to life. Spiderwort was blooming this spring. Asters and goldenrods put on a beautiful display in late summer, and by fall those annual plants had cured to provide a perfect fuel. We had a much more successful burn, this time with more flame height and (hopefully) enough intensity to start setting back the maple seedlings that were outcompeting the oaks. /features/janfebmar_2021\Iowa2_Big.jpg It’s always nice when anecdotal experience is backed by formal research, and our experience at Motor Mill seems in line with expectations derived from the more rigorous scientific research out there on the topic of fire in oak ecosystems. The Morton Arboretum in the Chicagoland area has a stretch of oak woodland they’ve burned every single year for the last 30 years. They’ve found that in that stand, the floral diversity dwarfs that of the adjacent woodlands.

The burned area counts over 10 plant species per square meter. On top of that, the burned plot has virtually eliminated invasive shrubs from much of its understory, except those individuals large enough to withstand or suppress fire underneath their own canopy.

For those concerned about the use of herbicides on their land, the Morton Arboretum presents a strong case for more aggressive application of fire in the woods. The repeated use of fire has led to a proliferation of plants adapted to handle and promote fire, and the suppression of species like maple which produces leaf litter less apt to carry a burn.

There is a trade off, however. The burn frequency at the Morton Arboretum may actually be hindering oak regeneration, since young oak seedlings don’t have the fire tolerance of their older, bigger relatives. Moreover, some research suggests burning too often can alter the soil chemistry in a way that hinders oaks.

The prep work for timber burns does require a little more effort. Small oak saplings should be protected by clearing flammable materials for a few feet around their base. Larger standing snags – great habitat for insects and cavity-nesting birds – might need a similar treatment to keep them from igniting even with the lower intensity of the flames.

But the results speak for themselves. Garlic mustard, multiflora rose, and even honeysuckle seem to evaporate with the regular occurrence of fire. The floral diversity – particularly in midsummer, when the more open canopy of a fire-dominated woodland allows more sunlight to the forest floor – plays host to a greater variety of insects and, by extension, insect eaters and the animals that eat insect eaters.

Fire managers must become avid weather watchers, and those seeking timber burns even more so. The national weather service maintains a very handy website for examining pertinent weather data and smoke dispersal conditions. The Eastern Area Coordinating Group also maintains a great online resource on wildfire conditions. We’ve found about 9-15% fuel moisture on the 10-hour fuels (leaf litter and small sticks), with a steady (not gusty) wind of 15-25 mph and a humidity around 30-50% ideal for executing successful timber burns. We’ve been able to add fire to our woodland management toolbox at Motor Mill, Bloody Run, and Becker West, and with each burn we find ourselves learning a little more about what it can do for those ecosystems and how it behaves.

It’s yet another reminder that for all our scientific advances, no amount of herbicides, fertilizers, or specialized equipment will outperform the tools mother nature has provided for thousands of years. Whenever practical, we do best when we integrate ourselves into the mosaic of natural elements, rather than adding extra variables.

On that front, I would add one more quote from Robin Wall Kimmerer’s fantastic book Braiding Sweetgrass: “The land is the real teacher. All we need as students is mindfulness.”

If you want to learn more about safely performing prescribed burns, check out the Iowa DNR’s resources. A good burn requires careful planning and a knowledgeable, experienced crew. It’s not the right tool for every situation, but if you take some time to learn fire’s effects, you might find it invaluable in helping you reach your goals for your woodland.

Looking Back On 2020

The mild November made it difficult to imagine the trials and tribulations of the Armistice Day Blizzard, so on Nov. 11 naturalist Abbey Harkrader breathed new life into the story with a wonderful program at the Osborne Nature Center. The program also went live on facebook to help people at home better appreciate the magic of modern meteorology.

The annual Motor Mill Bridge Lighting on Nov. 21 also got a little different flavor this year, with participants driving through the festooned historic site and taking home a bag of cookies to kick off the holiday season.

The CCCB also hosted its first Cedars for Celebration event on Nov. 28, inviting the public to help improve habitat and bag a wild-caught holiday tree at the same time. Many thanks to all who came out to enjoy a safe, socially distant activity on a beautiful Saturday!![]()